Jim, Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

Jim, Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

August 16, 2011 was the most beautiful day of the summer, and as a teacher with summers off, I was taking full advantage of it. I was home with my son Nikitas, who wouldn’t nap unless I was pushing him in the stroller. When he awoke, we sat on the ledge of our favorite fountain, mugging for selfies.

An hour later, I was getting dressed to go to the Phillies game when in the mirror I saw my face darkening to purple. My wife, Vana, rushed upstairs and watched in speechless terror. I decided it was too late to call 911, so I called my dad, a doctor, who advised me to take deep breaths.

As my face swelled, I looked at Vana and thought, I love you. And, I might be dying.

Minutes passed, and the flooding subsided. I said I was better now. My dad said go to the emergency room, now.

I went to Penn, where I was given an EKG and X-rays were taken. After midnight, a CAT scan was taken of my neck and chest. Later, Dr. Utley rose from behind the main desk and came to my room, holding the black-and-white image. She sat with me on the bed and pointed to two gray bands that appeared strangely narrowed. These were the crucial veins to the heart, she explained. “This could be fatal. We just don’t know what this is.” She leaned forward, as if to hug me. She gave me an encouraging smile and returned to her post. I called Vana, and the sound of her cry was one I’d never heard before. At three in the morning, I was taken for an MRI; inside the tube, I thought of Nikitas and me just hours earlier at the fountain on the Parkway.

When I was admitted the next day, Dr. Eric Goren, the young attending internist, explained that until other specialists studied the results of the MRI, I was going to be treated as if I had a clot. An IV was feeding a blood thinner into my wrist in hopes I wouldn’t suffer another “attack.” Later, Dr. Goren, who insisted I call him Eric, told me it wasn’t a clot causing the narrowing, but fibrosis—scarring. But veins didn’t form scar tissue in the area where mine apparently had. He said he was assembling the best possible team, including the highly regarded vascular surgeon Dr. Ed Woo. “He’s never seen this before,” Eric said. “None of us have.”

The next day, Eric brought in the chief of interventional radiology, Dr. Scott Trerotola, who explained that the only way to make a diagnosis was to do a biopsy—to enter the chest and take a piece of the scar tissue. He described how he would have to pierce the wall of the vein, then pull the fibrotic matter back through it. But the bleeding could be catastrophic.

Before Eric left for the night, he confessed he didn’t have a plan but refused to send me home. I was “the talk of the hospital,” he said. “You’ve stumped some very smart people who do not like to be stumped.”

On my fourth day, Dr. Woo said he was prepared to dismiss the need for a diagnosis. Whatever had caused the fibrosis was unknown, and I would just have to adjust to my new “idiopathic” condition. He explained how “collateral veins” formed when obstructed blood found new pathways. He said, “I think you’re going to be okay.” Back in the world, I tried to convince myself that it was only a matter of time before I adjusted to my new condition.

Vana and I joined my parents at their beach house, where I scrutinized the distended veins on my neck. I wanted to believe that collateral veins were forming, but I feared the stenosis was worsening. Under the starlight, Vana and I stood at the edge of the ocean; a grown boy and his father passed by us like ghosts of the future life I feared I wouldn’t live. I wailed into Vana’s hair, howling my desperate longing to be alive to see my own son running.

On Saturday of Labor Day weekend, I packed a bag and announced that it was time for me to return to the hospital. The swelling and discomfort in my head and neck were unignorable. Within hours I was admitted, got an EKG and CAT scan, and was informed by two young doctors, who were unlucky enough not to be on holiday, that what I had was a clot. They scheduled an MRI to confirm it was a clot.

But hours later, after one desperate phone call led to another, Drs. Woo and Trerotola were tracked down at the beach, and soon the two were in communication with each other, assessing the latest test results on their personal computers and sending word back to Philly that what I had was not a clot and what I needed was not an MRI but a venogram, which Dr. Trerotola would administer first thing Tuesday morning.

Before the sun came up, I was wheeled into a large cold room. Vana and I kissed goodbye, before I was sedated and drifted off into a kind of wakeful oblivion, aware of the needle entering near my neck, dye entering my bloodstream. When I awoke, I was staring at a glowing triptych two feet high and twice as wide. Magnified in black and white was an area of my internal anatomy that I recognized as freakishly abnormal, my eyes drawn to the vertical black line that looked like a hot dog with a toothpick stuck on top. The toothpick formed the base of a Y. The arms of the Y were the brachiocephalic veins, which I knew branched toward the jugular veins on each side of the neck. But what this toothpick was, I didn’t understand.

Dr. Trerotola explained that what we were looking at was where the X-ray had picked up the dye injected into the bloodstream. Anything black indicated blood flow. Anything else appeared as white light. The hotdog was the SVC—the superior vena cava—the main vein entering the heart. The toothpick indicated the amount of blood flowing into my SVC from the brachiocephalic veins. To be clear, the toothpick should be as big as the hotdog. The negative space around the toothpick—just white, borderless light—was where the obstruction was, the fibrosis we wouldn’t yet call a mass or a tumor because these words suggested malignancy, and this obstruction did not appear to be malignant; it was too symmetrical, like a perfect doughnut, unlike malignant tumors, which are asymmetrical and ugly.

The doctors all agreed that it was too risky to do a biopsy. Even if Dr. Trerotola managed to procure some bit of the mass, the pathologists could find it to be no more than unidentifiable fibrosis; or the mass could be disturbed by the needle and break into pieces that spread into the bloodstream. The second option, to remain in observation mode, wasn’t really an option, since I had five- or ten-percent blood flow through the toothpick and no one knew how long the vein might stay open. The final option was surgery, but no one knew what the surgical strategy would be, much less what the prognosis would be.

That afternoon, Dr. Woo visited my room. Though my breathing remained unrestricted, it seemed I was being strangled from the inside, a little more so each hour, the backed-up blood pressing at my eyes and throat. I was sitting next to Vana on my bed, my parents in chairs, getting the straight truth from Dr. Woo, who told us there was nothing left that they could do. He said the end would not be pleasant; it would not be a good life, for the brief time I might survive. He sat with us in silence. I understood I was going to die soon. I was here with my wife and parents, who would bury me. I wanted to save them from such grief. Vana and I cried together on the bed. “I’m sorry,” Dr. Woo said, and left the room.

In my white cotton gown, I made my way toward my parents and hugged them. My father cried, and said, “I’m sorry, son.” Then he set his blue eyes on me and said, “Tomorrow, more research.” It was an expression of desperation, but also of infinite and illogical hope. “We go on,” he said.

I had told the attending internist how I fantasized about sitting with a radiologist in front of all the films and asking the questions I’d developed, to reconcile the contradictions between the earliest readings and theories, and those from the past week. So, when she entered the room smiling, I could see she was determined to push back against the forces pressing in on my shrinking world. She informed us that Dr. Miller, the top chest radiologist, was willing to speak with me. We rose to our feet with some vague hope emerging, if only at the prospect of comprehending the dreadful fact of my untreatable syndrome.

On our way to the elevator, we saw Dr. Trerotola, who did an about-face and walked with us to the basement, where Dr. Miller sat before three large screens featuring images of my superior vena cava. Mouse at his fingertips, Dr. Miller escorted us into the three-dimensional world of my chest. Our eyes traveled down a roller-coaster vein that arrived at a massive white doughnut with a small dark hole. We were gazing at the future cause of my death. No autopsy would provide a better view than the one I was getting now. This was living proof that I couldn’t survive much longer with such limited flow.

Dr. Miller said, “Whatever it is, it needs to come out.” He looked at Dr. Trerotola and said, “Now this is a question for Dr. Pochettino.” I thought, Who is this Dr. Pochettino?

On our way out, I asked Dr. Miller how many times he’d sat here like this with a patient.

“You’re it,” he said.

Hours later, Dr. Alberto Pochettino entered my room and introduced himself as a transplant surgeon. After reviewing our grim options, he said, “What I will do is take it all out and reconstruct the SVC with a post-organic composite made of pig intestine, which I’ve used to patch hearts and lungs.” He looked at Vana and said, “Your husband will be in critical care for two days after surgery, then another week in the hospital, and back to work in three months.” It seemed too fantastic, that I might live, let alone return to normal life. He said, “We can do the surgery tomorrow or Friday. I would not wait until Monday.”

I looked at Vana and at my parents, then back at Dr. Pochettino. “So there’s hope?” I asked. He said, “There is always hope.”

In the O.R., I was gone for five hours, to a place of no thought or memory, despite the electric saw that split the sternum, the machine that pumped the heart, the hands that snipped and stitched—all these magnificent feats accomplished for my sake while I existed in a blankness that might prove eternal.

I awoke to the staggering misery of having a tube down my throat. I tried to scream, recalling the pre-surgery instructions to rank my pain from one to ten. I heard Vana’s soothing voice, but, somehow, she couldn’t hear me screaming, “Ten! Pain!” She turned away and said, “I think he’s saying something.”

It was then that my sense of humor returned, along with the full recognition that I was alive and feeling the pain that was promised upon my awakening, and I was howling at the absurd and hilarious and beautiful world, “Ten! Ten! Pain! Pain!” with Vana’s ear at my mouth, as she tried to hear what in my head was a blood-curdling scream. Finally, she announced, “Ten, he’s saying. His pain is a ten, he means.”

Days later, once I was out of the ICU and into my own room, Dr. Dan Landsburg, a hematologist fellow, came to discuss the pathology report. He sat down and said, “So, you have lymphoma.” It took me a moment to register that it was even cancer that we were talking about. He said I had “diffuse large B-cell lymphoma” and he’d hooked me up with a cool young oncologist. I asked, “Who’s the best? Not the coolest?” He smiled and said, “Steve Schuster” and he’d see what he could do.

Back home, I seemed to be healing just fine, relieved of my SVC syndrome for one glorious week. Then I felt that dreadful swelling in my head. I was re-admitted to the hospital, where Dr. Pochettino reminded me that he’d crafted the graft to measure over twenty millimeters in circumference, seven wider than the existing SVC, figuring it would shrink to fifteen, forming a perfect cylinder. For now, I was surviving with a five-millimeter opening, but there was no telling how much more it might narrow, or how rapidly. Then he said he had done more research and concluded that chemo would be safe after one month of healing, which meant we would get started on Friday.

Before I went home, Dr. Pochettino informed us that in the latest CAT scan the graft had shrunk to less than five millimeters. He concluded that the cause of the narrowing was the imperfect healing of the graft—something chemo couldn’t fix, if anything could.

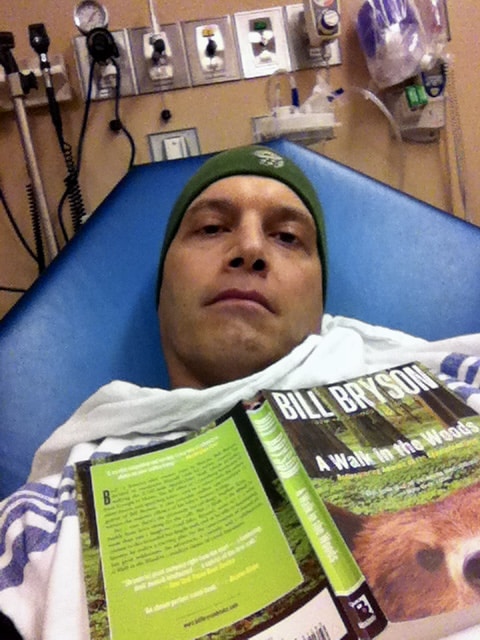

Every three weeks for the next three months, I got chemo—each treatment followed by a predictable cycle, which included one week of crippling nausea, one week of feeling half normal, and one week of malaise, while I braced myself for neutropenia. By November I was bald and making the best of it. By December I was hairless, bloated, and insufferably temperamental from prednisone. I got fevers, sinus infections, and herpetic ulcers; and finally, after my sixth and final treatment, my temperature spiked at three A.M. and I was on the phone with Dr. Schuster, who said, “Well, it figures, it’s your last treatment, and now you get neutropenic.”

In the ER, I got the test results. My white cell count was .6, and the neutrophil count was zero—zero infection-fighting white blood cells. The nurse reminded me that, without antibiotics, I could become septic and die. When that didn’t happen, after two days of lying sequestered in a remote private room, I was headed home, on an uncertain road to recovery.

In March I visited my classroom, eager to return. In April, I was back for good. I choked back tears at a pep rally, standing at the edge of the gym, a thousand kids shrieking with joy. I was dumbfounded by the miracle of life, and I didn’t want to lose this feeling.

In June, Dr. Pochettino announced he was leaving Penn for the Mayo Clinic. I was his last patient, his last appointment, on his last day at Penn. He encouraged me to make an appointment with Dr. Trerotola to discuss angioplasty, though he couldn’t say for sure it would be an option. He smiled and said, “We’re all still learning from you on this.”

In August, Dr. Trerotola was surprised to see I wasn’t puffed up, but relieved it wasn’t the emergency he’d anticipated when he saw I’d made an appointment. He read the recent CAT scan report and said that my SVC was down to three millimeters. Together we looked at the latest scans in amazement. I said it was hard to imagine any blood making it through there.

He said, “We don’t have to understand it. It’s working. Let’s not try to fix what’s not broken.” When I thanked him for his caution, he grinned and said he was known as a risk-taker. Only then did I appreciate what tremendous restraint he’d been exercising all along.

I remain aware of the miraculous reality of life, of the breath that sustains me, of my ever-pumping heart, of my body with all its confounding mysteries that scans can’t explain.

At the one-year post-chemo PET scan, Dr. Schuster brought a plate of baklava; and the rest is history—give or take a frightful bout of night sweats and symptoms that keep me from doing strenuous physical activities that I don’t miss doing.

Eventually, I managed to get past tearing up at every marvelous moment, though I remain aware of the miraculous reality of life, of the breath that sustains me, of my ever-pumping heart, of my body with all its confounding mysteries that scans can’t explain.

At the park near our house in the city, two-year-old Nikitas and I headed down the street to watch the Little League game. Deep in the outfield, I threw him pitches that he whacked at with his fat plastic bat. He watched the boys on the dirt diamond in the distance and said he was going to play, too, “when I get big.” He asked me if I was going to play—“when you get small?” When I get small. I contemplated the innocent genius of this question. Of course, through eyes that don’t know death, life must at some point begin again. “Yes,” I lied, “when I get small,” and for a moment we existed in a field where time bends back on itself and we grow younger after we’ve grown older and we get to be here together forever.